Travail et puissance d’une force.

Introduction :

I. Travail d’une force constante

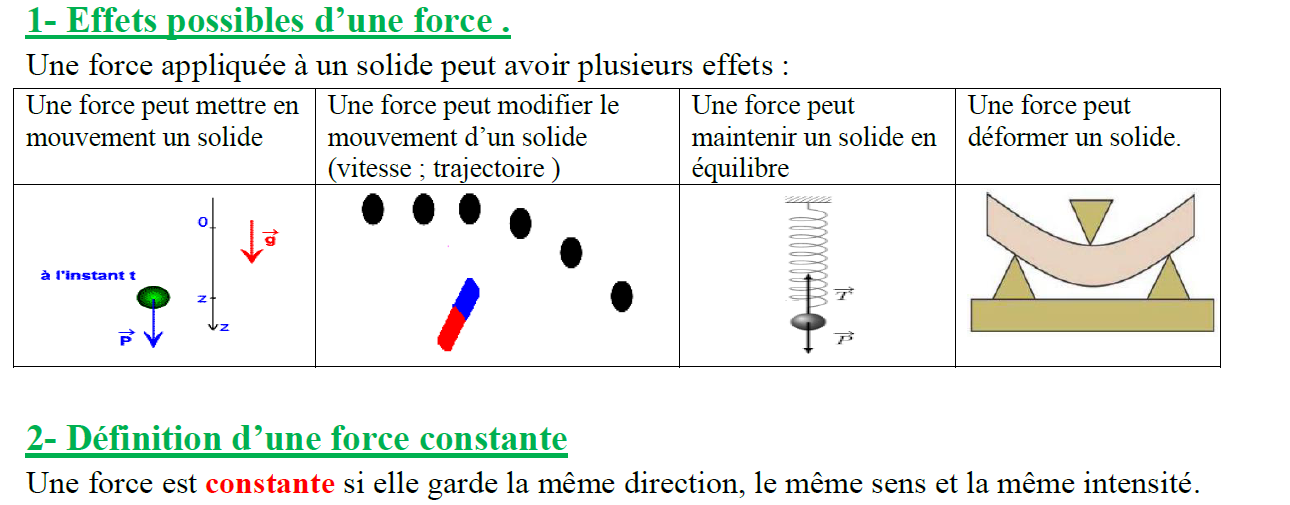

1- Effets possibles d’une force

Une force appliquée à un solide peut avoir plusieurs effets :

2- Définition d’une force constante

Une force est constante si elle garde la même direction, le même sens et la même intensité.

| Une force peut mettre en mouvement un solide | Une force peut modifier le mouvement d’un solide (vitesse ; trajectoire ) | Une force peut maintenir un solide en équilibre | Une force peut déformer un solide. |

|  |  |  |

II. Travail d’une force constante dans le cas d'un solide en translation ou en rotation

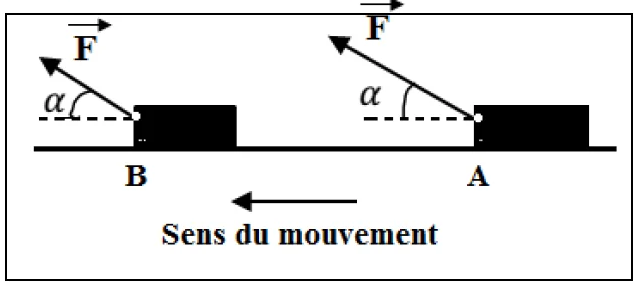

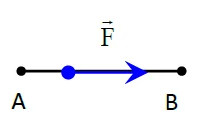

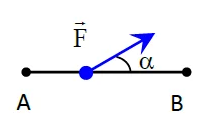

1. Travail d’une force constante pour un déplacement rectiligne

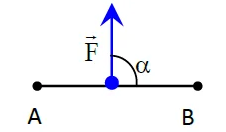

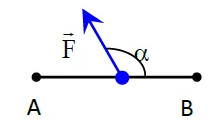

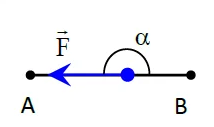

Le travail d’une force constante $\overrightarrow{\mathrm{F}}$ pour un déplacement rectiligne $\overrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}$ de son point d’application noté $\underset{A \rightarrow B}{W}(\vec{F})$ est le produit scalaire du vecteur force $\vec{F}$ et du vecteur déplacement $\overrightarrow{A B}$.

$\begin{aligned} & {\underset{A}{A \rightarrow B}}^{( }(\vec{F})=\vec{F} \cdot \overrightarrow{A B} \\ & W_{A \rightarrow B}(\vec{F})=F \cdot A B \cdot \cos \alpha\end{aligned}$

Avec $\alpha$ l’angle entre les vecteurs $\vec{F}$ et $\overrightarrow{A B}$

L’unité de travail est le Joule (symbole J).

2. Travail moteur, travail résistant

Le travail d’une force est une grandeur algébrique.

Un travail positif est un travail moteur et un travail négatif est un travail résistant.

| α = 0° | α < 90° | α = 90° | 90° < α ≤ 180° | α = 180° |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |  |

| $\mathrm{W}_{\mathrm{AB}}(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{F}})$ positif : Travail moteur | $\mathrm{W}_{\mathrm{AB}}(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{F}})$ positif : Travail moteur | $\mathrm{W}_{\mathrm{AB}}(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{F}})$ = 0 | $\mathrm{W}_{\mathrm{AB}}(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{F}})$ négatif : Travail résistant | $\mathrm{W}_{\mathrm{AB}}(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{F}})$ négatif : Travail résistant |

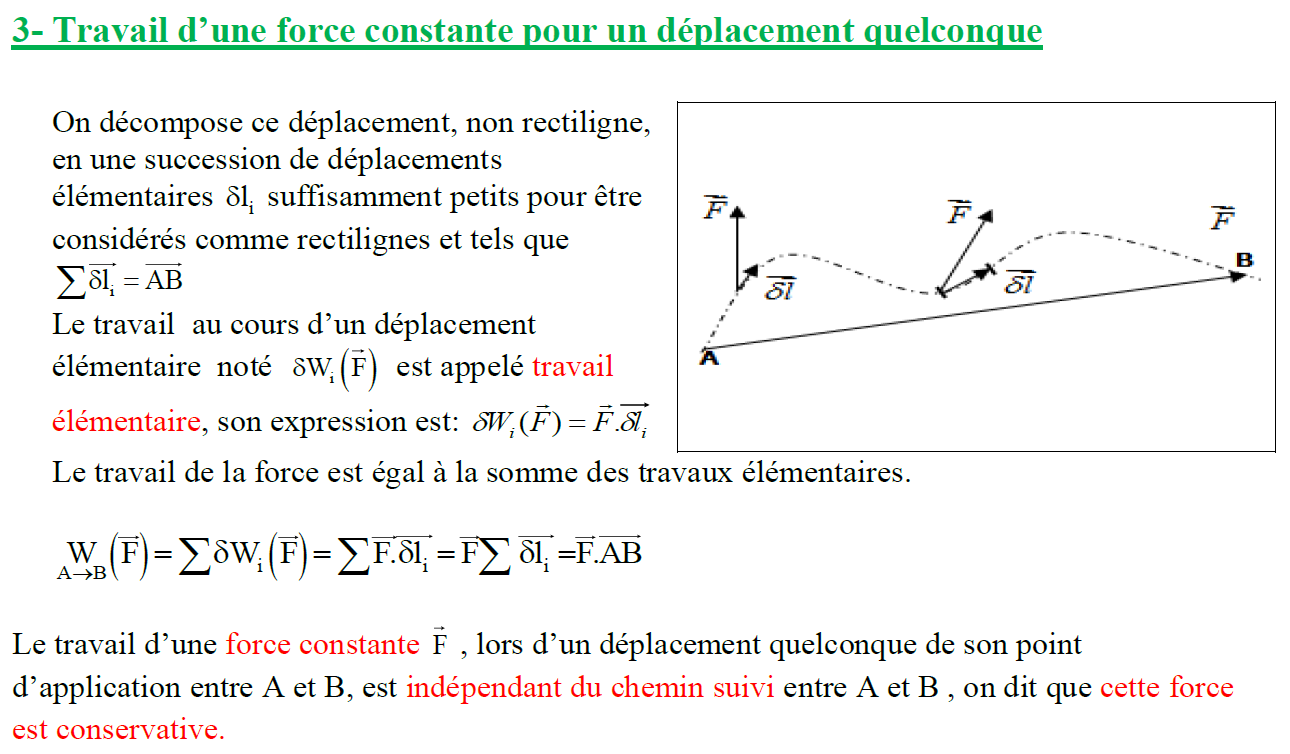

3. Travail d’une force constante pour un déplacement quelconque

On décompose ce déplacement, non rectiligne,

en une succession de déplacements élémentaires $\delta 1_i$ suffisamment petits pour être considérés comme rectilignes et tels que $\sum \overrightarrow{\delta \mathrm{l}_1}=\overrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}$

Le travail au cours d’un déplacement élémentaire noté $\delta \mathrm{W}_{\mathrm{i}}(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{F}})$ est appelé travail élémentaire, son expression est: $\delta W_i(\vec{F})=\vec{F} \cdot \overrightarrow{\delta_i}$ Le travail de la force est égal à la somme des travaux élémentaires.

$$

\underset{A \rightarrow B}{ }(\vec{F})=\sum \delta W_i(\vec{F})=\sum \vec{F} \cdot \delta_i=\vec{F} \sum \overrightarrow{\delta I_i}=\vec{F} \cdot \overrightarrow{A B}

$$

Le travail d’une force constante $\overrightarrow{\mathrm{F}}$, lors d’un déplacement quelconque de son point d’application entre A et B, est indépendant du chemin suivi entre A et B , on dit que cette force est conservative.

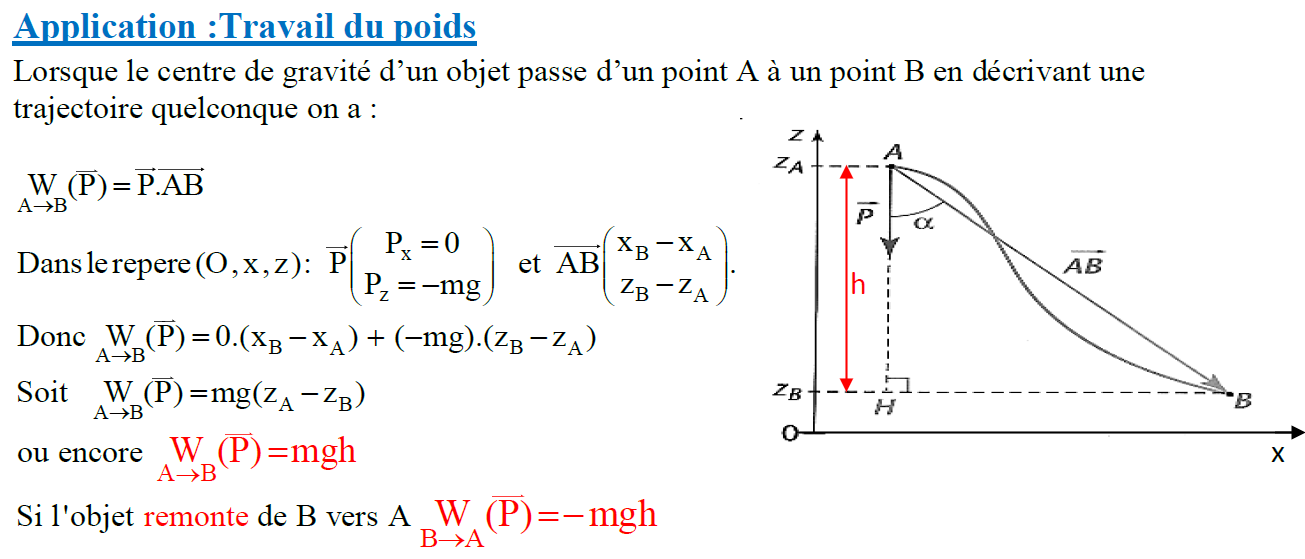

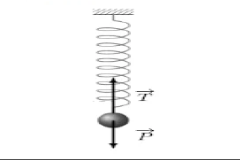

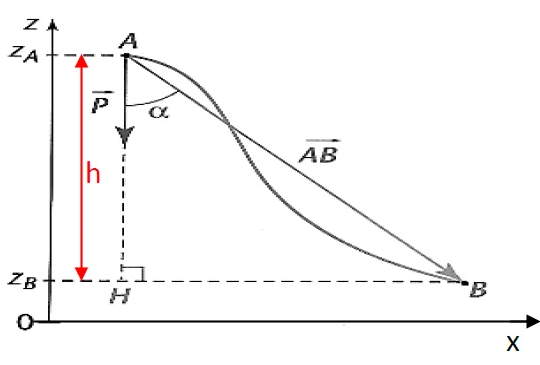

Application: Travail du poids

Lorsque le centre de gravité d’un objet passe d’un point A à un point B en décrivant une trajectoire quelconque on a :

$$

\underset{\mathrm{A} \rightarrow \mathrm{~B}}{ }(\stackrel{\rightharpoonup}{\mathrm{P}})=\overrightarrow{\mathrm{P}} \cdot \stackrel{\mathrm{AB}}{ }

$$

Danslerepere $(O, x, z): \vec{P}\binom{P_x=0}{P_z=-m g}$ et $\overrightarrow{A B}\binom{x_B-x_A}{z_B-z_A}$.

Donc $\underset{\mathrm{A} \rightarrow \mathrm{B}}{\mathrm{W}}(\overline{\mathrm{P}})=0 \cdot\left(\mathrm{x}_{\mathrm{B}}-\mathrm{x}_{\mathrm{A}}\right)+(-\mathrm{mg}) \cdot\left(\mathrm{z}_{\mathrm{B}}-\mathrm{z}_{\mathrm{A}}\right)$

Soit $\quad \underset{\mathrm{A} \rightarrow \mathrm{B}}{\mathrm{W}}(\mathrm{P})=\mathrm{mg}\left(\mathrm{z}_{\mathrm{A}}-\mathrm{z}_{\mathrm{B}}\right)$

ou encore $\underset{\mathrm{A} \rightarrow \mathrm{B}}{\mathrm{W}}(\mathrm{P})=\mathrm{mgh}$

Si l’objet remonte de B vers A $\underset{\mathrm{B} \rightarrow \mathrm{A}}{\mathrm{W}}(\overline{\mathrm{P}})=-\mathrm{mgh}$

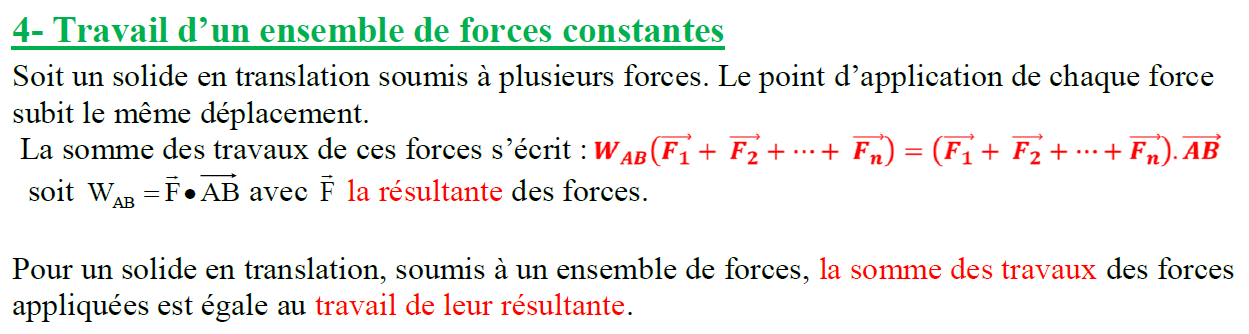

4. Travail d’un ensemble de forces constantes

Soit un solide en translation soumis à plusieurs forces. Le point d’application de chaque force subit le même déplacement.

La somme des travaux de ces forces s’écrit : $W_{A B}\left(\overrightarrow{F_1}+\overrightarrow{F_2}+\cdots+\overrightarrow{F_n}\right)=\left(\overrightarrow{F_1}+\overrightarrow{F_2}+\cdots+\overrightarrow{F_n}\right) \cdot \overrightarrow{A B}$

soit $\mathrm{W}_{\mathrm{AB}}=\overrightarrow{\mathrm{F}} \bullet \overrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}$ avec $\overrightarrow{\mathrm{F}}$ la résultante des forces.

Pour un solide en translation, soumis à un ensemble de forces, la somme des travaux des forces appliquées est égale travail de leur résultante.

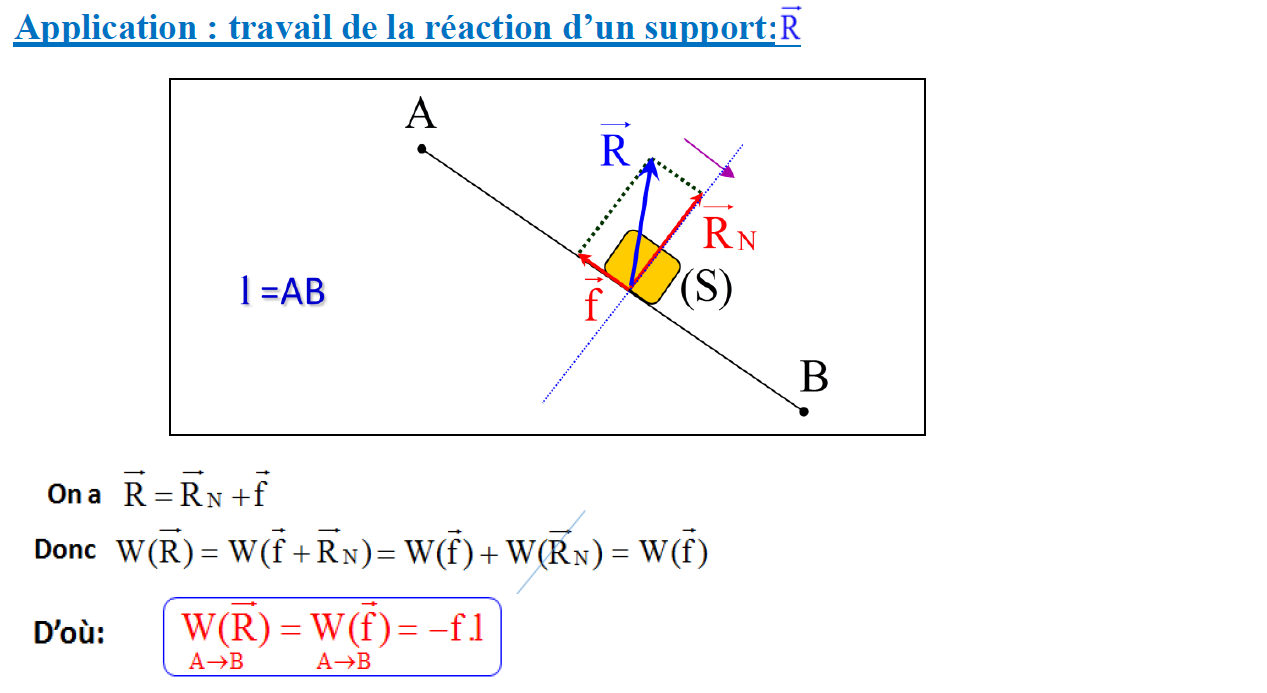

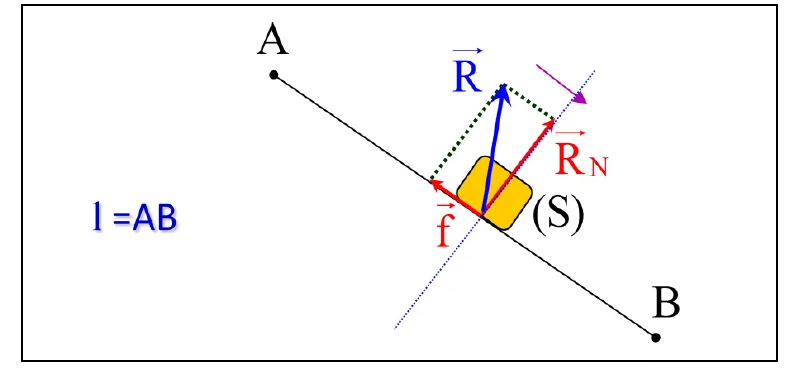

Application : travail de la réaction d’un support: $\overrightarrow{\mathrm{R}}$R}}$

Ona $\quad \vec{R}=\vec{R}_N+\vec{f}$

Ona $\quad \vec{R}=\vec{R}_N+\vec{f}$

Donc $\mathrm{W}(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{R}})=\mathrm{W}\left(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{f}}^{+} \overrightarrow{\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{N}}\right)=\mathrm{W}\left(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{f}}_{\mathrm{f}}\right)+\mathrm{W}\left(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{N}}\right)=\mathrm{W}\left(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{f}}_{\mathrm{f}}\right)$

D’où: $\quad \underset{A \rightarrow B}{W(\vec{R})}=\underset{A \rightarrow B}{W}(\vec{f})=-f .1$

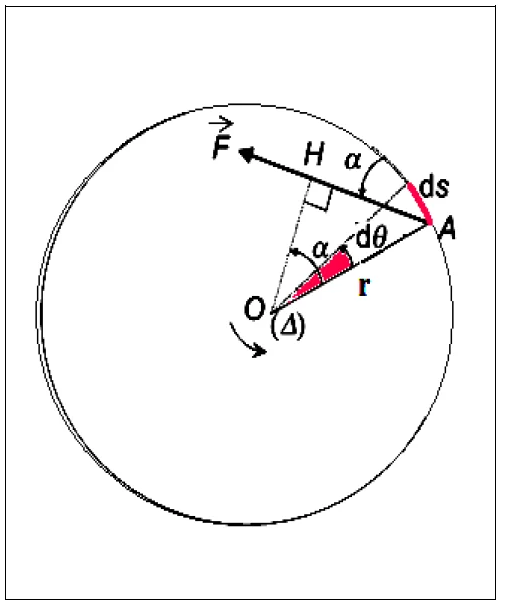

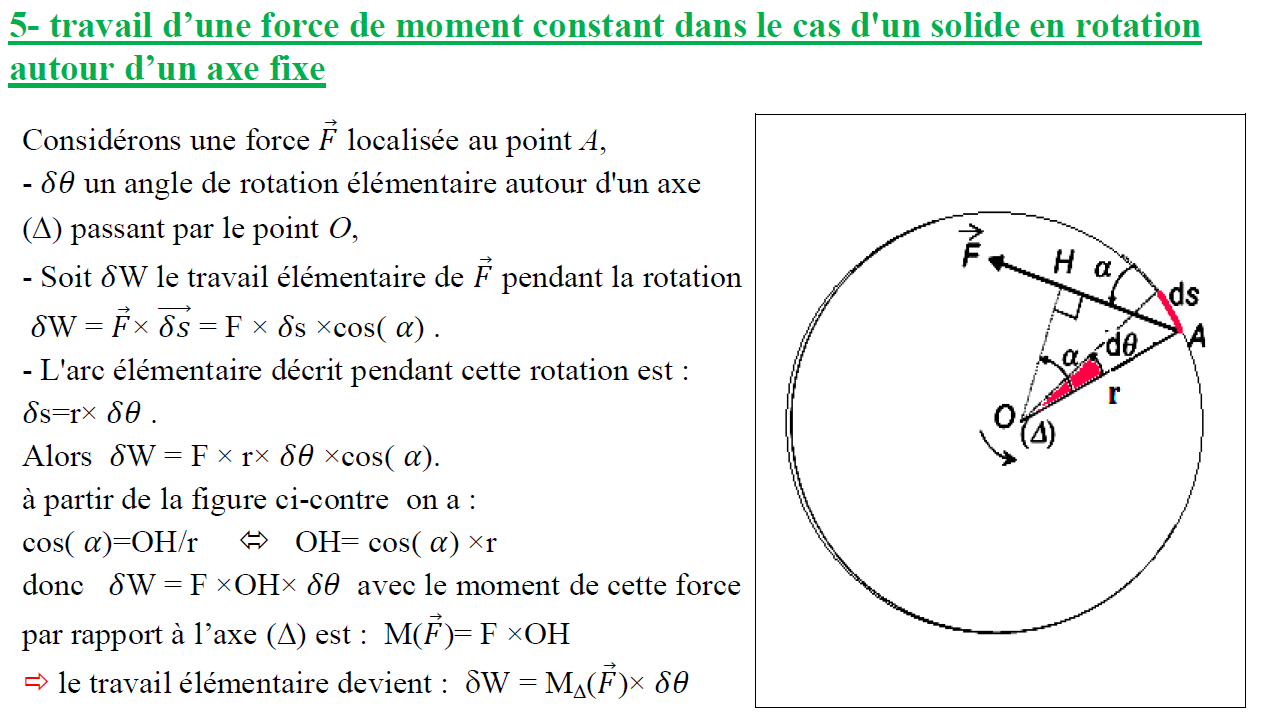

5. travail d’une force de moment constant dans le cas d’un solide en rotation autour d’un axe fixe

Considérons une force $\vec{F}$ localisée au point $A$,

– $\delta \theta$ un angle de rotation élémentaire autour d’un axe

$(\Delta)$ passant par le point $O$,

– Soit $\delta \mathrm{W}$ le travail élémentaire de $\vec{F}$ pendant la rotation $\delta \mathrm{W}=\vec{F} \times \overrightarrow{\delta s}=\mathrm{F} \times \delta \mathrm{s} \times \cos (\alpha)$.

– L’arc élémentaire décrit pendant cette rotation est : $\delta \mathrm{s}=\mathrm{r} \times \delta \theta$.

Alors $\delta \mathrm{W}=\mathrm{F} \times \mathrm{r} \times \delta \theta \times \cos (\alpha)$.

à partir de la figure ci-contre on a :

$$

\cos (\alpha)=\mathrm{OH} / \mathrm{r} \Leftrightarrow \mathrm{OH}=\cos (\alpha) \times \mathrm{r}

$$

donc $\delta \mathrm{W}=\mathrm{F} \times \mathrm{OH} \times \delta \theta$ avec le moment de cette force par rapport à l’axe ( $\Delta$ ) est : $\mathrm{M}(\vec{F})=\mathrm{F} \times \mathrm{OH}$

$\Rightarrow$ le travail élémentaire devient : $\delta \mathrm{W}=\mathrm{M}_{\Delta}(\vec{F}) \times \delta \theta$

– Lorsque le solide tourne d’un angle $\Delta \Theta$ le travail de force $\vec{F}$ est : $\mathrm{W}(\vec{F})=\sum \delta W=\sum M_{\Delta}(\vec{F}) \times \delta \theta=M_{\Delta}(\vec{F}) \times \sum \delta \theta$ car $M_{\Delta}(\vec{F})$ est constant.

Et puisque $\sum \delta \theta=\Delta \theta$ alors : $\mathrm{W}(\vec{F})=M_{\Delta}(\vec{F}) \times \Delta \theta$

Le travail d’une force de moment constant dans le cas d’un solide en rotation autour d’un axe fixe est $\mathrm{W}(\vec{F})=M_{\Delta}(\vec{F}) \times \Delta \theta$

III. Puissance d’une force :

1. La puissance movenne

Si, pendant une durée $\Delta t$, une force $\overrightarrow{\mathrm{F}}$ effectue un travail $\mathrm{W}(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{F}})$, la puissance moyenne

$\mathrm{P}_{\mathrm{m}}$ de cette force est $\quad \mathrm{P}_{\mathrm{m}}=\frac{\mathrm{W}(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{F}})}{\Delta \mathrm{t}}$ avec :

$\mathrm{P}_{\mathrm{m}}$ en watts (W), W( $\overrightarrow{\mathrm{F}}$ ) en joules (J) et $\Delta t$ en secondes (s).

Remarque : Lorsque l’intervalle de temps $\Delta t$ est très petit, la puissance moyenne devient une puissance instantanée.

2. La puissance instantanée

On appelle puissance instantanée d’une force $\vec{F}$ la variation instantanée de son travail au cours du temps : $P(t)=\frac{\delta W}{\delta t}$

Puisque $\delta W=\vec{F} \times \overrightarrow{\delta l}$ alors $P(t)=\vec{F} \times \frac{\overrightarrow{\mathcal{S} . I}}{\mathcal{\delta} . t}$ or $\vec{v}(t)=\frac{\overrightarrow{\mathcal{S} . I}}{\mathcal{S} . t}$

La puissance instantanée de la force $\vec{F}$ est :$P(t)=\vec{F} \cdot \vec{V}(t)$

Ou

$\mathrm{P}(\mathrm{t})=\mathrm{F} \times \mathrm{V} \times \cos (\vec{F} ; \vec{V})$

3. Puissance instantanée d’une force agissant sur un corps en rotation

L’expression du travail est $\delta \mathrm{W}=M_{\Delta}(\overrightarrow{\boldsymbol{F}}) \times \delta \theta$ avec $M_{\Delta}(\overrightarrow{\boldsymbol{F}})$ moment de la force par rapport à l’axe de rotation.

La puissance instantanée $P(t)=\frac{\delta W}{\delta t}=\mathrm{M}_{\Delta}(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{F}}) \times \frac{\delta \theta}{\delta t}$ avec $\omega(\mathrm{t})=\frac{\delta \theta}{\delta \mathrm{t}}$ vitesse angulaire instantané à t .

La puissance instantanée d’une force s’exerçant sur un solide en rotation autour d’un axe fixe est égale à :

$P(t)=\mathrm{M}_{\Delta}(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{F}}) \times \omega(t)$