Vectors and translation

I- Direction and sense

1. The Direction :

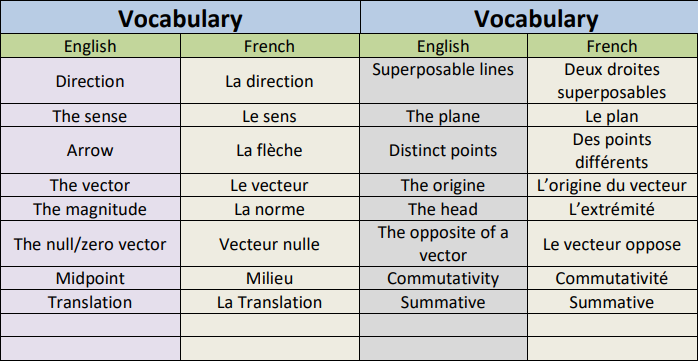

Exemple :

– We consider the following figures :

– The two lines (D) and (D’) are parallel lines or superposable lines, so they have the same direction

Définition :

▶ A line in the plane determine a direction

▶ Two lines (D) and (D’) have the same direction if (D) and (D’) are parallel lines or superposable lines.

▶ If Two lines (D) and (D’) are secants lines then the two lines (D) and (D’) haven’t the same direction.

Exemple :

– We consider the following figures :

– The two lines (d) and (d’) are parallel, so they have the same direction.

– The two lines ( $\Delta$ ) and ( d ) are secant lines, so they haven’t the same direction.

Remark :

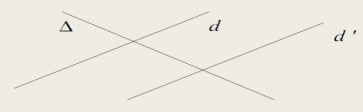

► Two distinct(different) points $A$ and $B$ determine one direction which is the line (AB) and all the parallel lines to the line $(A B)$.

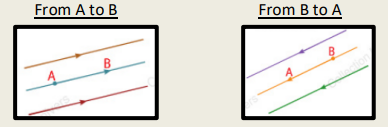

2. The sense :

Définition :

– We consider the line (AB) or (d)

– We can determine two possible senses in the line (AB)

▶ Sense 1 : From A to B.

▶ Sense 2 : From B to A.

Remark :

► Attention : the word direction in our daily life is confused with the sense, In MATH we choose the direction (the line) first then we choose the sense.

– Two distinct(different) points A and B determine in the direction of the line (AB) two opposites senses indicated with arrows,

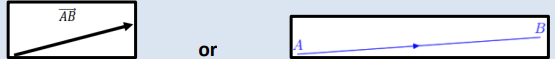

II- The vector

Définition :

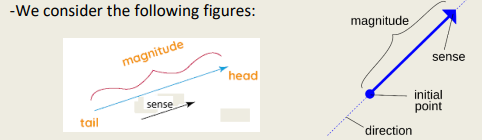

A vector is a geometrical entity ; it’s a combination of three things :

– A direction (a line) in space,

– A sense from the tail to the head.

– A positive number called its magnitude,

– Typically, a vector is illustrated as a directed straight line.

The vector in this example $\overrightarrow{A B}$ with :

✓ $\checkmark$ The direction of the vector $\overrightarrow{A B}$ which is the line ( AB )

✓ $\checkmark$ The sense of the arrow, from the point A to the point B ,

✓ $\checkmark$ The magnitude of $\overrightarrow{A B}$ given by the length of the distance AB .

✓ $\checkmark$ The origine (Tail or origine point) which is the point A

✓ $\checkmark$ The head (the extremity or the arrowhead) which is the point B

Exemple :

Remark :

❖ A vector can be represented by a line with an arrow pointing towards its sense and its length represents the magnitude of the vector.

❖ Vectors are represented by arrows; they have initial points and terminal points.

❖ Every two distinct points A and B determine two vectors : $\overrightarrow{A B}$ and $\overrightarrow{B A}$

$\begin{aligned} & \text { The vector } \overrightarrow{A B} \text { is } \\ & \text { characterized by: }\end{aligned}\left\{\begin{array}{l}\text { The direction: }(\mathrm{AB}) \\ \text { The sense: } \mathrm{A} \Rightarrow \mathrm{B} \\ \text { The magnitude : the distance } \mathrm{AB}\end{array}\right.$

1. The null/zero vector :

Définition :

► A vector with no direction and no sense and magnitude equal to 0 is known as null or zero vector

► Every point in the plane determines a vector called null vector

► We write : $\overrightarrow{A A}=\overrightarrow{0}$

► If $\overrightarrow{A B}=\overrightarrow{0} \quad$ Then $\quad \mathbf{A}=\mathbf{B}$ (The two points $\mathbf{A}$ and $\mathbf{B}$ are the same point)

► If $\overrightarrow{A B}=\overrightarrow{0} \quad$ Then $\quad \overrightarrow{A B}=\overrightarrow{A A}=\overrightarrow{B B}=\overrightarrow{0}$

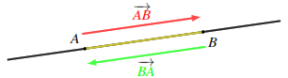

2. The opposite of a vector :

Définition :

► A and B are two distinct points of the plane.

► We have : $\overrightarrow{A B}+\overrightarrow{B A}=\overrightarrow{0}$

► The vector $\overrightarrow{B A}$ is the opposite vector of the vector $\overrightarrow{A B}$

And we write: $\overrightarrow{B A}=-\overrightarrow{A B}$

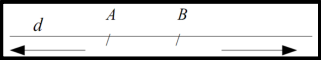

Exemple :

We consider the following figure :

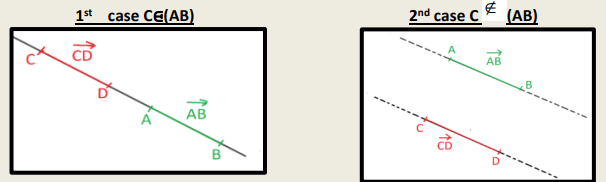

III- Equal vectors

Définition :

► Two vectors are equal if they have:

– The same direction

– The same sense

– The same magnitude

► $\overrightarrow{A B} \overrightarrow{C D}$ if:

– $\overrightarrow{A B}$ and $\overrightarrow{C D}$ have the same direction; ( $\mathbf{A B}$ )//(DC)

– $\overrightarrow{A B}$ and $\overrightarrow{C D}$ have the same sense; $[\mathrm{AB})$ and $[\mathrm{DC})$ have the same sense

– $\overrightarrow{A B}$ and $\overrightarrow{C D}$ have the same magnitude; $\mathbf{A B}=\mathbf{D C}$

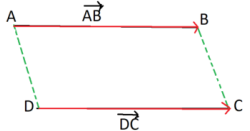

Exemple :

– We consider the following figures :

Remark :

❖ The equality $\overrightarrow{A B} \overrightarrow{C D}$ regroup three conditions, the three conditions (the direction, the sense, the magnitude) should be verified to say that: $\overrightarrow{A B} \overrightarrow{C D}$

Propriety :

If $\overrightarrow{A B}=\overrightarrow{D C}$

Then : $\quad-\mathrm{ABCD}$ is a parallelogram

$-[\mathrm{AC}]$ and $[\mathrm{BD}]$ have the same midpoint

Exemple :

– We consider the following figure :

– We have $\overrightarrow{A B}=\overrightarrow{D C}$

– Then $(\mathrm{AB}) / /(\mathrm{DC})$ and $\mathrm{AB}=\mathrm{DC}$

– So : ABCD is a parallelogram

– The diagonals $[A C]$ and $[B D]$ have the same midpoint

Propriety 2 :

If ${A B C D}$ is a parallelogram Then $\quad \overrightarrow{A B}=\overline{D C}$

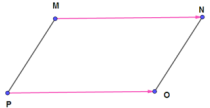

Exemple :

– We consider the following figure :

– We have MNOP is a parallelogram

– Then $\overrightarrow{M N}=\overrightarrow{P O}$ and $\overrightarrow{M P}=\overrightarrow{N O}$

Propriety 3 :

If $\overrightarrow{A B} \overrightarrow{A D}$ Then $B=D$

Propriety 4 :

If $\overrightarrow{A B}=\overrightarrow{B C}$ Then B is the midpoint of the segment $[\mathrm{AC}]$

If $\overrightarrow{B A}=\overrightarrow{C B}$ Then B is the midpoint of the segment $[\mathrm{AC}]$

IV- The sum of vectors

1. The sum of vectors (Triangle method) :

Définition :

► The vectors addition (Triangle method)

– To add two vectors $\overrightarrow{A B}$ and $\overrightarrow{B C}$ we follow the steps :

Step 1 : Draw the vector $\overrightarrow{A B}$

Step 2 : At the head (the arrowhead) of $\overrightarrow{A B}$, draw the vector $\overrightarrow{B C}$.

Step 3 : Join the beginning of $\overrightarrow{A B}$ to the head (the arrowhead) of $\overrightarrow{B C}$

► This is vector $\overrightarrow{A B}+\overrightarrow{B C}=\overrightarrow{A C}$

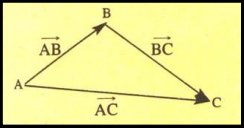

Exemple :

– We consider the following figure :

– $\overrightarrow{A B}+\overrightarrow{B C}=\overrightarrow{A C}$

The sum of two vectors is a vector

2. The sum of vectors (Parallelogram method) :

Définition :

► The vectors addition (Parallelogram method)

– The sum of the two vectors $\overrightarrow{A B}$ and $\overrightarrow{A C}$ is the vectors $\overrightarrow{A E}$ such as :

► ABEC is a parallelogram

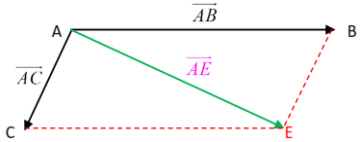

Exemple :

– We consider the following figure :

– $\overrightarrow{A B}+\overrightarrow{A C}=\overrightarrow{A E}$

The sum of the two vectors is the diagonal of

the parallelogram

Proprieties :

► $\overrightarrow{A B}, \overrightarrow{C D}$ and $\overrightarrow{E F}$ are non null vectors

► The sum of vectors is commutative :

$$

\overrightarrow{A B}+\overrightarrow{C D}=\overrightarrow{C D}+\overrightarrow{A B}

$$

► The sum of vectors is summative :

$$

\overrightarrow{(\overrightarrow{A B}+\overrightarrow{C D})}+\overrightarrow{E F}=\overrightarrow{A B}+(\overrightarrow{C D}+\overrightarrow{E F})

$$

► The sum of the zero vector :

$$

\overrightarrow{A B}+\overrightarrow{0}=\overrightarrow{0}+\overrightarrow{A B}=\overrightarrow{A B}

$$

3. CHASLES theorem :

Rule :

– We have :

$$

\overrightarrow{A B}+\overrightarrow{B C}=\overrightarrow{A C}

$$

Exemple :

– We consider the following figure :

– $\overrightarrow{A B}+\overrightarrow{B C}=\overrightarrow{A C}$

Exemple 2 :

Without drawing simplify the following expressions :

$\begin{aligned} \overrightarrow{E F}+\overrightarrow{G E}+\overrightarrow{F G} & =\overrightarrow{E F}+\overrightarrow{F G}+\overrightarrow{G E} \\ & =\overrightarrow{E G}+\overrightarrow{G E} \\ & =\overrightarrow{E E} \\ & =\vec{O}\end{aligned}$

$\begin{aligned} \overrightarrow{A B}-\overrightarrow{B D}+\overrightarrow{C A}-\overrightarrow{C B} & =\overrightarrow{A B}+\overrightarrow{D B}+\overrightarrow{C A}+\overrightarrow{B C} \\ & =\overrightarrow{A B}+\overrightarrow{B C}+\overrightarrow{C A}+\overrightarrow{D B} \\ & =\overrightarrow{A C}+\overrightarrow{C A}+\overrightarrow{D B} \\ & =\overrightarrow{A A}+\overrightarrow{D B} \\ & =\vec{O}+\overrightarrow{D B} \\ & =\overrightarrow{D B}\end{aligned}$

4. The sum of many vectors :

Rule :

– We have :

$$

\overrightarrow{A B}+\overrightarrow{B C}=\overrightarrow{A C}

$$

5. The Midpoint of a segments :

Rule :

– We have: $\overrightarrow{A M}+\overrightarrow{B M}=\overrightarrow{0}$

$$

\begin{aligned}

& \overrightarrow{M A}+\overrightarrow{M B}=\overrightarrow{0} \\

& \overrightarrow{A M}=\frac{1}{2} \overrightarrow{A B} \\

& \overrightarrow{A B}=\mathbf{2} \times \overrightarrow{A M}=\mathbf{2} \times \overrightarrow{M B}

\end{aligned}

$$

V- Vectors Subtract

Définition :

► $\overrightarrow{A B}$ and $\overrightarrow{C D}$ are non null vectors

► To subtract two vectors we add the opposite vector of the second vector

$\begin{aligned} \overrightarrow{A B}-\overrightarrow{C D}= & \overrightarrow{A B}+(-\overrightarrow{C D}) \\ & =\overrightarrow{A B}+\overrightarrow{D C}\end{aligned}$

► $\overrightarrow{A B}-\overrightarrow{C D}$ is called the difference between the two vectors $\overrightarrow{A B}$ and $\overrightarrow{C D}$

Exemple :

– We have : A, B and C are three distinct points.

– Let’s calculate $\overrightarrow{A B}-\overrightarrow{A C}$

$\begin{aligned} \overrightarrow{A B}-\overrightarrow{A C} & =\overrightarrow{A B}+(-\overrightarrow{A C}) & & \rightarrow \text { Using the definition of subtract } \\ & =\overrightarrow{A B}+\overrightarrow{C A} & & \rightarrow \text { Using the definition opposite vectors } \\ & =\overrightarrow{C A}+\overrightarrow{A B} & & \rightarrow \text { We can change the order of vectors } \\ & =\overrightarrow{C B} & & \rightarrow \text { Using CHASLES theorem }\end{aligned}$

VI- Vectors Multiplication

Rule :

– We have : $\overrightarrow{A B}+\overrightarrow{A B}+\ldots \ldots \ldots \ldots+\overrightarrow{A B}=\mathbf{n} \times \overrightarrow{A B}$

Exemple :

– We have : $\quad \overrightarrow{A B}+\overrightarrow{A B}+\overrightarrow{A B}=3 \times \overrightarrow{A B} \quad$ and $\quad(-\overrightarrow{M N})+(-\overrightarrow{M N})=(-2) \times \overrightarrow{M N}$

Remark :

❖ $\overrightarrow{A B}$ is a non null vector and $\mathbf{n}$ is an integer; $\mathbf{n} \times \overrightarrow{A B}=(-\mathbf{n}) \times \overrightarrow{B A}$

VII- Translation

Définition :

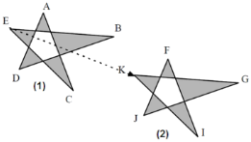

► When we drag(move) a figure (1) from point E to point K in a straight line without turn it, to get the figure (2)

line without turn it, to get the figure (2)

– We say that : the figure (2) is the image of the figure (1) with translation that transforms the point $E$ to the point K or with respect to the Vector $\overrightarrow{E K}$

Définition :

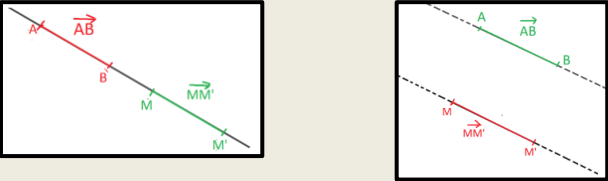

► A, B and M are distinct points of the plane :

►$\overrightarrow{A B}$ is a non null vector

► We say that: the point M’ is the image of point M with translation that transforms the point $\mathbf{A}$ to the point $\mathbf{B}$ (or with respect to the Vector $\overrightarrow{A B}$ ) if $\quad \overrightarrow{A B}=\overrightarrow{M M^{\prime}}$

► We note : $t_{\overline{A B}}(\mathbf{M})=\mathbf{M}^{\prime}$

► It means that :

– The two lines (AB) and (MM’) have the same direction

– The sense from $M$ to $M$ ‘ is the same sense from $A$ to $B$

– The two distances AB and $\mathrm{MM}^{\prime}$ are equal

Exemple :

$\overrightarrow{A B}$ is a non null vector. M and $\mathrm{M}^{\prime}$ are points such $\overrightarrow{M M^{\prime}}=\overrightarrow{A B}$

– the point $\mathbf{M}^{\prime}$ is the image of point $\mathbf{M}$ with translation that transforms the point $\mathbf{A}$ to the point B (or with respect to the Vector $\overrightarrow{A B}$ )

Remark :

❖ $\overrightarrow{A B}$ is a non-null vector. M and $\mathrm{M}^{\prime}$ are points such $\overrightarrow{M M^{\prime}}=\overrightarrow{A B}$

❖ the point $\mathbf{M}^{\prime}$ is the image of point $\mathbf{M}$ with translation that transforms the point $\mathbf{A}$ to the point $B$ (or with respect to the Vector $\overrightarrow{A B}$ )

❖ Means that : $\mathbf{A B M} \mathbf{M}$ is a parallelogram

VIII- Vocabulary